Sanora Babb is unlikely to be your immediate answer when asked “who wrote the Great American Dust Bowl novel?” Instead, you’ll probably think of John Steinbeck, and his classic The Grapes of Wrath. That’s what I thought, at least, before I saw this fascinating Twitter thread by Skyler Schrempp. It turns out that Sanora Babb and her own novel Whose Names Are Unknown might very well hold this title — and the two books have more in common than being brilliant takes on a terrible time.

The more I looked into her life, the more awestruck I became. An artist, a journalist, an activist, and a key figure in the midcentury literary landscape, Sanora Babb ought to be far better known than she is now. So let’s get to it.

Early Years

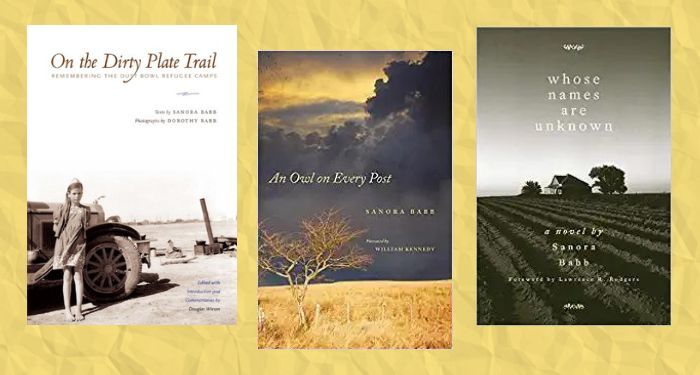

Sanora Babb was born April 21, 1907, to Walter and Jeanette Babb, in Leavenworth, Kansas. Because of Walter’s restlessness, the family (including her sister Dorothy, two years younger than herself) moved around a lot. In 1913, they settled in a “one-room dugout home on a broomcorn farm in Baca County, Colorado.” Sanora chronicled the difficulties of this childhood in her fictionalized memoir An Owl on Every Post (1970).

The isolation also meant that she was 11 years old by the time she first attended school. Catching up quickly, she was valedictorian of her high school class, although she was barred from giving a speech due to her father’s bad reputation. After attending the University of Kansas for a year, she ended up graduating from Garden City Junior College in 1926. She obtained her teaching certificate and worked as a teacher for a year, but her heart lay elsewhere. The Garden City Herald, which had published several of her previous writings, soon offered her a job as a reporter.

Sanora’s ambitions were bigger, however, and in 1929 she moved to Los Angeles in order to find journalistic work. Her timing wasn’t the best: the beginnings of the Great Depression made themselves felt in the lack of available opportunities. Soon, though, she found a job as secretary for Warner Brothers and, later, as scriptwriter for KFWB radio station.

The 1930s

This was a busy decade for Sanora. She brought her sister Dorothy to Los Angeles. She had a brief affair with Ralph Ellison before she met Chinese American filmmaker James Wong Howe, whom she married in a civil ceremony in Paris in 1937. The marriage wasn’t recognized in the United States, however, due to the anti-miscegenation laws in place. As a result, and due to a combination of Howe’s traditional Chinese values and Hollywood’s “moral code,” the couple wouldn’t live together until they were able to legally marry in California in 1948. Even then, it took them three days to find a judge willing, albeit grudgingly and offensively, to marry them.

In 1937, she temporarily moved to London, where she co-edited the political magazine The Week, along with Claud Cockburn. The following year she returned to the U.S., where she volunteered to work for the Farm Security Administration and aid those displaced by the Dust Bowl. Sanora’s role was assistant to Tom Collins, the migrant camp manager.

Her duties were varied and primarily organizational. They consisted in fulfilling basic needs for the families and educating the workers on labor rights. But this experience also planted the seed of an idea: she began to take meticulous notes in order to write a novel about the situation. Her sister Dorothy, a photographer, took pictures when she visited.

In the meantime, Sanora wrote and published essays in The Clipper and The Masses. But by 1939, she was working on what would become Whose Names Are Unknown. She sent several chapters of the novel to Random House, notorious for not publishing debut novels…and they immediately offered her a contract.

Whose Names Are Unknown remained unpublished for decades though. Why?

Whose Names Are Unknown, The Grapes of Wrath, and the World’s Worst Boss

You know Ask a Manager‘s Worst Boss of the Year award? Tom Collins would’ve qualified. Unbeknownst to Sanora, Collins shared her notes with John Steinbeck, who was also working on a novel about the migrant workers displaced by the Dust Bowl. Steinbeck had met Collins when he visited the camps in order to interview the residents. It is unknown whether he knew who the owner of the notes was, and that she had not agreed to have them shared. Either way, The Grapes of Wrath was published in April 1939, becoming an instant success.

After this, Random House ended the contract with Sanora, stating that publishing another novel about the situation now would be anticlimactic. They offered to buy another novel from her, but the novel she had wanted to publish was no longer in the cards. Every other publishing house she sent the book to turned it down.

Disillusioned, she wouldn’t write another novel for several years.

From the 1940s Onward

That is not to say that she stopped being involved in the literary scene: not only did she continue to write poetry, essays, and short stories, she also served as the West Coast secretary of the League of American Writers. She was on the editorial board of the League’s journal, The Clipper, and its successor, The California Quarterly. In this role, she was instrumental in the first publications of writers like Ray Bradbury, B. Traven, Aimé Césaire, and more. As usual, Sanora was invested in making sure that other voices were heard.

Because she was a member of the Communist Party during eleven years, she was under scrutiny by the House Un-American Activities Committee. Afraid of damaging her husband’s career, she moved to Mexico City. It was there that she began to draft her second novel, The Lost Traveler, published in 1958.

She returned to Los Angeles in 1951, where she continued to write and advocate for what she believed in. During the ’50s and ’60s, she met with “a writers’ group that included Bradbury, Esther McCoy, Sid Stebel, Bonnie Barrett Wolfe, C. Y. Lee, Peg Nixon, Richard Bach, and Dolph Sharp.”

The following decades saw Sanora produce a large output of writing, mostly in short-form pieces. Many were compiled in anthologies The Dark Earth and Other Stories of the Depression (1987) and The Cry of the Tinamou (1997), and poetry compilation Told in the Seed (1998).

But the biggest moment of her career occurred in 2004, when she was 97 years old: Sanora finally published Whose Names Are Unknown. It received instant critical acclaim, becoming a finalist for both the 2005 Spur Award and the 2005 PEN Center USA Literary Award.

Sanora Babb died December 31, 2005, in Hollywood, California. It makes me smile to know that she got to see her first novel published after all, and to exuberant praise at that. As a result, for the first time, her entire published work is now available for purchase.

I don’t know about you, but I fully intend to take advantage of that fact.