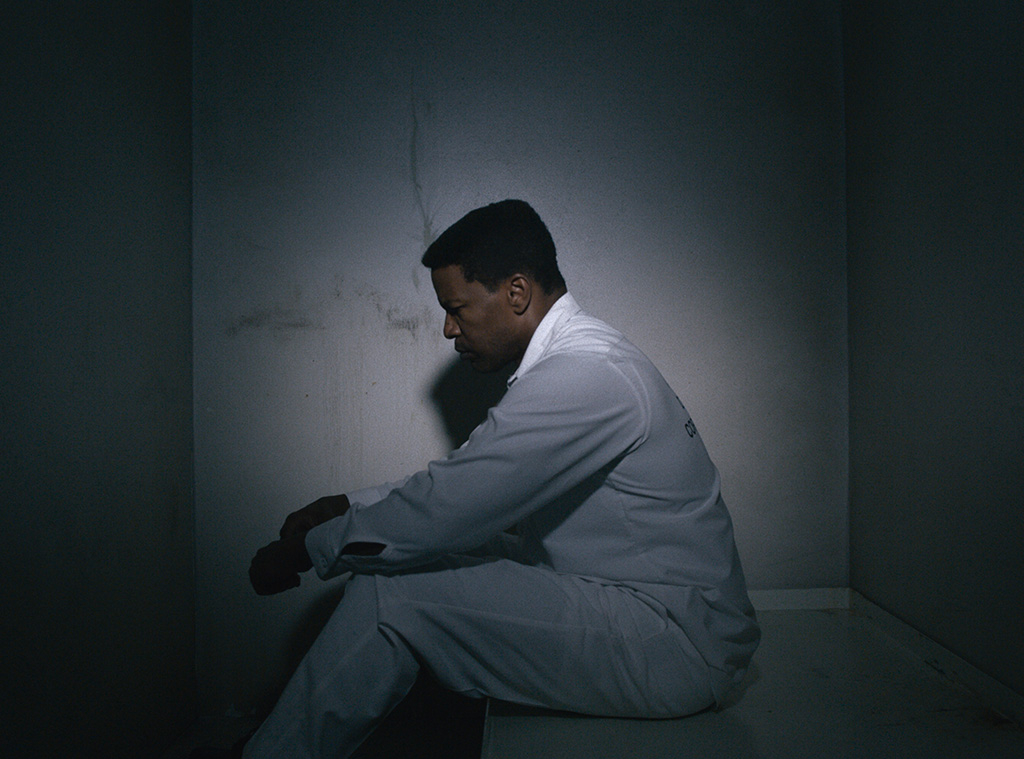

Jake Giles Netter/Warner Bros.

There’s a reason Jamie Foxx is calling his new film Just Mercy “one of the most important movies that I’ve ever been a part of.”

And why co-star and producer Michael B. Jordan felt, as he told Variety in October, “a sense of responsibility to tell this story, to make sure as many people as possible could see this film. And why, when fellow co-star Brie Larson learned of the story the film would be telling, it “just gave [her] this fire inside.” And why director Destin Daniel Cretton, when finishing the book written by Bryan Stevenson that the film would be based on, sent to him by his longtime producer Gil Netter, “wanted to be a part of it any way I could.”

And why former President Barack Obama put it on his shortlist of favorite films of 2019.

And that’s because the story of Walter McMillian, a black Alabama man wrongfully convicted in 1988 of the brutal murder of 18-year-old white woman Ronda Morrison despite zero physical evidence tying him to the case and an air-tight alibi, and the dogged and ultimately successful plight to exonerate him after six years spent on death row is shamefully a very true one, offering a sobering look into the ways in which the American criminal justice system often fails poor and minority communities alike.

While Stevenson’s 2014 memoir of the same name is about the lawyer and social justice activist, who took home the People’s Champion Award at the 2018 People’s Choice Awards among his many, many distinctions, tells the story of his work as the executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Ala., a non-profit dedicated to providing a defense for anyone in the state sentenced to the death penalty, as it’s the only one in the country that does not provide legal assistance to people on death row, it was the chapters on his work on behalf of McMillian that Cretton told Buzzfeed News he devoured in one sitting and convinced him the true story needed to be told on the big screen.

It’s not hard to see why.

After Morrison’s body was found under a rack of clothing in the Jackson Cleaners in Monroeville, Ala., bludgeoned, strangled and shot three times in the back on November 1, 1986, the murder went unsolved for months, putting newly elected sheriff Tom Tate under a lot of pressure to find the person responsible for the heinous crime. But when police arrested Ralph Meyers on suspicion of murdering another woman in a nearby country, Tate began to present his case.

Courtesy Warner Bros. Pictures

Investigators told Myers that they believed he’d also killed Morrison and that they had witnesses who would testify that he’d committed the crime alongside McMillian, a married pulpwood worker with no criminal record other than a misdemeanor charge stemming form a barroom fight who’d gained a bit of notoriety in his community for having an affair with a white woman, Karen Kelly. (His son had also married a white woman.) Myers eventually told the police the two had driven to the cleaners, with McMillian the only one to go inside. In a taped confession, he alleged he’d heard several popping sounds and then entered the building, where he saw Morrison dead.

That was enough for Tate, who quickly arrested McMillian, portrayed by Foxx in the film, in June of 1987. The accused explained to the Sheriff that he couldn’t have done it because he was at a church fish fry at the time of the murder, something plenty of witnesses could attest to. According to Pete Earley‘s book Circumstantial Evidence: Death, Life, and Justice in a Southern Town, Tate reportedly replied, ”I don’t give a damn what you say or what you do. I don’t give a damn what your people say either. I’m going to put 12 people on a jury who are going to find your goddamn Black ass guilty.”

In an unusually cruel move, McMillian was immediately sent to death row, where he spent 15 months before he even had his day in court. (Myers, who was jointly indicted with McMillian on December 11, 1987, pleaded guilty as a conspirator in the murder and received a 30-year prison sentence.) When that day finally came, on August 15, 1988, presiding Judge Robert E. Lee Key, Jr. had the trial moved from a county that was 40 percent black to Baldwin County, where 86 percent of the residents were white. Shockingly, it lasted just a day and a half.

On August 17, 1988, a jury of 11 white citizens and one African-American found McMillian “guilty of the capital offense charged in the indictment” and recommended a life sentence based the testimony of Myers and three others, ignoring multiple alibi witnesses who testified under oath that McMillian was at the fish fry and the fact that there was no physical evidence to implicate him in the crime.

Jake Giles Netter/Warner Bros.

It got worse from there. On September 19, Judge key overruled the recommendation of life in prison and imposed the death penalty, remarking at the time that McMillian “deserved to be executed for the brutal killing of a young lady in the first full flower of adulthood.”

That was all it took to gain the attention of Stevenson, then 28 and the director of the newly formed Alabama Capital Representation Resource Center in Montgomery, in November, who took on the task of appealing the case despite a threatening call from Key himself. “What was so surreal about this case was that all these things that weren’t supposed to happen kept happening,” he explained on NPR’s Fresh Air in 2016. “You know, I went to the prison to meet him first, this condemned man. And he told me that he’d been placed on death row for 15 months before the trial. And I thought, you know, that’s not what’s supposed to happen. And then I got back to my office, and I got a call from a man named Robert E. Lee Key, who was the judge who had condemned him to time, who told me that I shouldn’t take the case, that this was not the kind of case that I should get involved with.”

And yet, he did anyway, certain that the wrong man had been sentence to death. “I went to the community and met dozens of African-Americans who were with this condemned man at the time the crime took place 11 miles away who absolutely knew he was innocent,” he continued. “And they told the police, and the police didn’t do anything.”

But while Stevenson, portrayed by Jordan in the film, was determined to prove his client’s innocence, the state of Alabama was equally determined to make it has hard as possible for him to do so. From 1990 to 1993, four appeals were denied by the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals.

However, beginning in 1992, things began to come to light that eventually made it impossible to ignore McMillian’s case.

Courtesy Warner Bros. Pictures

Meyers told McMillian’s trial counsel that the testimony he’d given “agaisnt McMillian was false,” confessing that “he knew nothing about the crime, that the was not present when the crime was committed, that he had been told what to say by certain law enforcement officers, and that he had testified falsely against McMillian because of pressure form the officers.”

Despite this, a 1992 petition for a new trial alleging constitutional violations was denied.

A year later, though, even more evidence pointing to gross miscarriages of justice was unearthed. It was revealed that McMillian’s truck, allegedly seen by witnesses at the scene of the crime, hadn’t been converted to a “low-rider” until six months after the crime took place, despite claims that it had been seen in that modified state. The two witnesses recanted their testimony and admitted that they’d perjured themselves at trial. Furthermore, it emerged that District Attorney Theodore Pearson had failed to disclose evidence that pointed to McMillian’s innocence, a witness who’d seen Morrison alive at the time when prosecutors claimed he’d killed her.

Not only that, but after obtaining the original recording of Myers’ confession, it was revealed that the tape’s reverse side contained a recording of a conversation between Myers and the police in which he complained about being forced to implicate McMillian, a man he didn’t even know.

“It was pretty surreal. They did coerce the witnesses to testify falsely against him and for some bizarre reason tape-recorded some of these sessions,” Stevenson told NPR. “So you hear this tape where the witness is saying, you want me to frame an innocent man for murder, and I don’t feel right about that. And the police officers are saying, well, if you don’t do it, we’re going to put you on death row, too. And they actually did put the testifying witness on death row for a period of time until he agreed to testify against Mr. McMillian. Other witnesses were given money in exchange for their false testimony.”

With the taped conversation unearthed, new D.A. Thomas Chapman, who had not been a part of the original case, reportedly told Stevenson, ”I want to do everything I can so that your client will not have to spend a single day more than he already has on death row. I feel sick about the six years that [McMillian] has spent in prison and the part I played in keeping him there.”

On February 23, 1993, in his fifth appeal to the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals, the judges unanimously ruled to reverse McMillian’s conviction and grant him a new trial. Stevenson then filed a motion to dismiss all charges, which was granted the following week.

Courtesy Warner Bros. Pictures

After his exoneration, on April 1, 1993, McMillian spoke before the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee about the dangers of the death penalty. ”There are many things that concern me as I sit here today. I am excited and happier than I can describe to be free. At times, I feel like flying,” he began. “However, I am also deeply troubled by the way the criminal system treated me and the difficulty I had in proving my innocence. I am also worried about others. I believe there are other people under sentence of death who like me are not guilty.”

“If federal courts do not permit death row prisoners to prove their innocence, even after many years on death row, and prevent wrongful executions, the hope of many innocent people on death row will be crushed,” he continued. “Justice is forever shattered when we kill an innocent man.” (As the film states in its sobering closing moments, for every nine people executed in this country, one innocent person has been exonerated, a truly astonishing rate of error.)

While his restored freedom was certainly a victory, the wins all but stopped there. Despite joining the defense’s quest to free McMillian, Chapman would never concede that there had been a “deliberate effort to frame” the man, claiming his exoneration “proved the system worked.” Tate was permitted to remain in office until his retirement in 2018. And after McMillian filed a civil lawsuit against him and other state and local officials, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against him, holding that a county sheriff couldn’t be sued for monetary damages. He was forced to settle with other officials for an undisclosed amount, instead.

McMillian returned home, resuming work as a tree trimmer, but two years later, he broke his neck while trimming a tree and went on partial disability, working part-time taking in junk cars for scrap metal. In a 2000 profile in The New York Times Magazine, he admitted he found it difficult not to be angry.

Courtesy Warner Bros. Pictures

“Sometimes I just want to leave here and never come back,” he told the publication. “A lot of people tell me, ‘Man, I’d leave.’ I tell them: ‘This is my home. I’m innocent.’ If I leave, first thing people say is: ‘He’s guilty. He left.’ I don’t see no reason I should leave my hometown.”

He also revealed that he often ran into the very same police officers who had played a part in his wrongful imprisonment. '” never got an apology. I see them—the cops—all the time. I see them on the street, at the fruit stand, they say, ‘Hey, Johnny, how ya doing?’ They’ll wave, just as good as anybody, like nothing happened. Every time I see one, I speak to them just like they speak to me. Ain’t no sense in me being mad,” he explained.

Sadly, McMillian was soon diagnosed with dementia, thought to have been brought on by the trauma of his time on death row, during which he watched as eight others were executed, smelling their flesh burning from the electric chair . The dementia left him thinking he was right back there. “When that comes full circle – and he’s sick, and he’s in a hospital, and he’s saying to me, you got to get me off death row again, it’s heartbreaking,” Stevenson told NPR. “When innocent people are released, we just act like they should be grateful that they didn’t get executed. And we don’t compensate them many times. We don’t help them. We question them. We still have doubts about them. And I saw that create this early onset dementia.”

McMillian passed away on September 11, 2013.

Ultimately, the hope is that, in telling McMillian’s story, more people will engage in criminal justice reform. For his part, Stevenson told Variety he’s bracing for an uptick in requests for aid once the movie is seen by the masses. (It was given an awards-qualifying limited released on Christmas Day last year.) AS he told the trade publication, prior to the 2014 publication of his memoir, the EJI received 100 emails a week looking for legal help. After? 500. And he expect that to double with the film, which is now in wide release.

“What I have to figure out is how we’re going to meet the need,” he said. “There are so many mothers and siblings and spouses whose loved ones didn’t get the help they needed.”

As Stevenson told the Los Angeles Times in early January, ”Conviction integrity is the thing that we’re pushing all across the country. We want prosecutors to be able to open the door, when somebody says they’re innocent, examine it. Prove to us that they’re wrong. And if they’re right, then do something.”

Just Mercy is in theaters now.